In 2017, 9,2% of the world’s population was estimated to live in poverty (World Bank, 2020). That statement seems simple enough, but what does it actually mean? Based on what are these people considered poor? Is it their living circumstances, income or maybe wealth? Poverty data are shaped by the way poverty is defined, and in their turn shape poverty eradication efforts. Therefore, it is important to know the poverty indicators used by organizations like the World Bank.

That number of 9,2% is a World Bank estimate based on income: it is the share of people ‘living on less than 1,9 US dollars (in Purchasing Power Parity, PPP) per day’. But income is a very limited measure of poverty and wellbeing. As the 1990 Human Development Report of the United Nations Development Programme (UDNP) makes clear, dimensions other than income are also important in human lives (UNDP, 1990). Think for example about empowerment, health, safety, education and access to clean water.

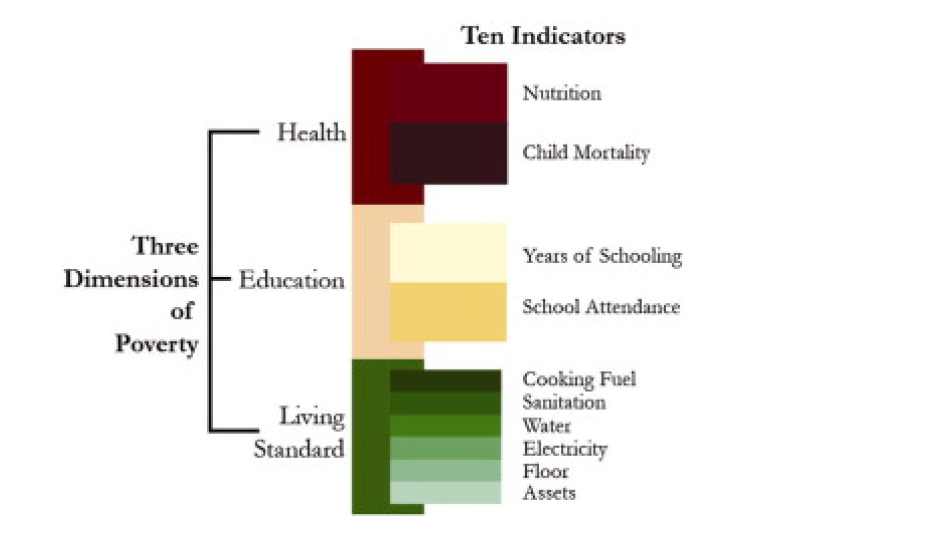

Having an income that supposedly suffices to meet these actual human needs, doesn’t necessarily mean that the needs are met. Alkire and Santos (2014) report that in four Sub-Saharan African countries (Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya and Niger), the amount of poor people according to the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI, see figure below) was 40% to 50% higher than when measured by the income poverty line. According to the World Bank Group, this percentage is true on a global scale as well (World Bank Group, 2018, p.9).

Dimensions and indicators of MPI. Source: Alkire and Santos, 2014

In 2018, the World Bank explicitly recognized the multidimensional nature of poverty in a report named Piecing Together the Poverty Puzzle (World Bank, 2018). Accordingly, the World Bank now reports data on multidimensional poverty. Despite this recognition, however, the focus of the World Bank’s efforts will remain to be on monetary poverty, as is stated in the conclusion. I want to show with two examples that indeed this is true.

First, the World Bank’s mission, to “end extreme poverty and promote shared prosperity in a sustainable way” is explained as “decreasing the percentage of people living on less than $1,90 a day to no more than 3%” and “increasing the incomes of the poorest 40 percent of people in every country” (World Bank 2020). Thus, the mission implies a purely monetary concept of poverty and prosperity.

Second, in the Human Capital Project, one of the World Bank’s priorities, investment in health and education is framed as a means to achieve monetary poverty reduction. The Human Capital Index is said to: “… quantify the contribution of health and education to the productivity of the next generation of workers. Countries can use it to assess how much income they are foregoing because of HC gaps…” (World Bank, 2020)

This contrasts with the notion that a lack of good education and health are dimensions of poverty in their own right.

To conclude, the World Bank recently adopted a new multidimensional poverty discourse. This broader view was not implemented in the organization’s core mission. It is yet to be seen to which extent the new discourse will have consequences for the World Bank’s actual activities.

Sources

Alkire, S., & Santos M.E. (2014). Measuring Acute Poverty in the Developing World: Robustness and Scope of the Multidimensional Poverty Index. World Development, 59, 251-274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.026.

Fukuda-Parr, S. (2019). Keeping Out Extreme Inequality from the SDG Agenda – The Politics of Indicators. Global Policy, 10, 61-69. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12602

UNDP. (1990). Human Development Report 1990: Concept and Measurement of Human Development. Retrieved from http://www.hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr1990

World Bank. (2018). Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2018: Piecing Together the Poverty Puzzle. Overview booklet. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/30418/211330ov.pdf

World Bank. (2020). https://www.worldbank.org/

Photo by Pujohn Das on Unsplash